Every month, we will put a spotlight on an aquatic invasive species (AIS) in a re-occurring monthly article. Check it out! This month, we highlight a well known invasive species: sea lamprey!

Sea Lamprey

Sea Lamprey (Petromyzon marinus) are a widely recognized aquatic invasive species to those who live on or near the Great Lakes. Native to the Atlantic Ocean, sea lamprey parasitizes on fish by sucking blood and other body fluids. Sea lamprey have remained largely unchanged for over 340 million years and have survived through over 4 major extinction events throughout Earth’s history.

Sea lampreys start their life cycles in streams and tributaries where non-parasitic sea lamprey larvae feed on plankton and detritus for three to ten plus years depending on environmental conditions and growth. The larvae then undergo a metamorphous into juveniles with mouths, eyes, and teeth and migrate to lakes. These parasitic juveniles spend the next 12-18 months feeding on fish. During the winter and early spring, these juveniles have gained weight and start searching for a suitable tributary to spawn. Once migrating back up a stream, sea lamprey mature into sexually spawning adults and reproduce in the late spring and summer. Shortly after reproducing, the adults die.

While classified as a fish, sea lamprey lack bony structures such as jaws but have a skeleton made of cartilage. At first glance, many people mistake the sea lamprey for an eel due to a similar body shape. However, the unique mouth of the sea lamprey is significantly different than an eel. The mouth is a sucking disk comprised of rows of sharp, horn-shaped teeth and a sharp tongue. The mouth allows the lamprey to suction onto its prey and use its teeth to grasp the prey while using the razor sharp tongue to rasp through fish scales. The saliva of the sea lamprey also contains an enzyme that prevents blood from clotting allowing the lamprey to continue feeding. In their native habitat of the Atlantic Ocean, fish have co-evolved with the lamprey and are usually able to survive a sea lamprey feeding. However, in the Great Lakes where sea lamprey did not co-evolve with fish, sea lamprey cause a much larger  impact by killing up to 40 pounds of fish over the sea lamprey’s 12-18 month feeding period. Fish in the Great Lakes very rarely survive a sea lamprey predation event due to the direct effect of the parasitic event or due to infection from the wound. Sea lamprey feed upon most of the large fish species in the Great Lakes including lake trout, lake sturgeon, walleye, bass, and the introduced Pacific salmonids.

impact by killing up to 40 pounds of fish over the sea lamprey’s 12-18 month feeding period. Fish in the Great Lakes very rarely survive a sea lamprey predation event due to the direct effect of the parasitic event or due to infection from the wound. Sea lamprey feed upon most of the large fish species in the Great Lakes including lake trout, lake sturgeon, walleye, bass, and the introduced Pacific salmonids.

Sea lamprey were first recorded in the Great Lakes in 1835 in Lake Ontario. Niagara Falls was a natural barrier that kept sea lamprey out of the other Great Lakes for thousands of years. However, construction and improvements to the Welland Canal to allow shipping routes between all the Great Lakes in the 1800s and early 1900s had the unforeseen additional impact of allowing sea lamprey to reach all of the Great Lakes by 1938. Due to excellent spawning habitat and natural abundances of host fish, combined with fecundity of the sea lamprey (every female can lay over 100,000 eggs), sea lamprey populations and impacts quickly grew throughout the Great Lakes.

The impact that the sea lamprey has had on the Great Lakes ecosystem has been well documented. Before the sea lamprey invasion, 15 million pounds of lake trout were harvested annually by the United States and Canada from the upper Great Lakes. By the late 1960s after sea lamprey populations had dramatically increased, the catch dropped dramatically to 300,000 pounds annually (about a 98% decrease). Of the fish that were caught, over 85% had sea lamprey attack wounds. Three endemic fish went extinct due to the sea lamprey. The decrease in larger fish allowed the invasive alewife population to explode followed by tremendous die-offs further changing the Great Lakes. The Great Lakes fishery has drastically changed and with it, the loss of thousands of jobs related to the Great Lakes region economy.

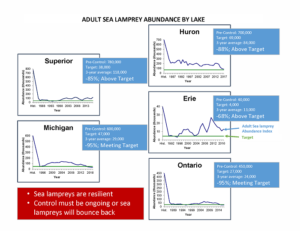

Since the mid-1950s, the Great Lakes Fishery Commission has worked to decrease the population of sea lamprey in the Great Lakes. Since lamprey need tributaries to spawn, the Commission targets lamprey during their reproductive phase. Lampricides (pesticides selective to sea lampreys) are used to kill adult and larval sea lampreys and are used in combination with barriers and traps to reduce the population of these invasive species. Compared with pre-control sea lamprey numbers, lamprey populations have decreased 95% due to the control efforts! While extremely effective, the sea lamprey control program on the Great Lakes is not able to eradicate lampreys from the Great Lakes due to the high number of quality spawning tributaries. Current estimates vary from lake to lake with a total abundance of less than 300,000 in the Great Lakes. However, ending the sea lamprey control program would result in a large bounce back of lamprey populations and with it, increased impact of this invasive species to the region’s lakes and economy.

While the Great Lakes have been invaded with sea lamprey, these invasive fish have not been found in the Winnebago System. The Fox River connects the Winnebago System to Green Bay but has an elevation change of 168 feet (Fig. 45). A series of 17 locks were built in the mid-1800s in order to allow for travel of people and goods up and down the river. These locks are maintained by the Fox River Navigational System Authority (FRNSA). In the late 1980s, one of the locks (Rapide Croche) was closed to prevent the spread of aquatic invasive species from Green Bay into Lake Winnebago, most notably, the sea lamprey. A sea lamprey barrier was also installed and FRNSA is required to maintain the barrier under Wisconsin Statute Chapter 237.10(1). FRNSA is currently exploring effective ways of opening navigation while preventing the spread of aquatic invasive species. If plans include the Rapide Croche lock, then according to Wisconsin Statute Chapter 237.10(2), ). “If the authority decides to construct a means to transport watercraft around the Rapide Croche lock, the authority shall develop a plan for the construction that includes steps to be taken to control sea lampreys and other aquatic nuisance species. The authority shall submit the plan to the department of natural resources and may not implement the plan unless it has been approved by the department.”

There are several native lamprey in Wisconsin including the Chestnut and American Brook lamprey and there have been reports of these lamprey in the Winnebago System in past years. However, these native lamprey do not deplete fish populations or cause the harm done by sea lamprey in the Great Lakes.

In Wisconsin, sea lamprey are classified as Restricted in all counties.

Want to help? HELP PREVENT THE SPREAD!

Every time you come off the water, make sure to follow these steps to stop the spread of faucet snails and other aquatic invasive species:

* Inspect boats, trailers, push poles, anchors, and other equipment for attached aquatic plants or animals.

* Remove all attached plants or animals

* Drain all water from boats, motors, livewells and other equipment

* Never move live fish away from a waterbody

* Never release aquarium plants or animals into your local waterways

Follow the Fox Wolf Watershed Alliance’s Winnebago Waterways Program on our Winnebago Waterways Facebook page or @WinnWaterways on Twitter! You can also sign-up for email updates at WinnebagoWaterways.org.

Questions? Comments? Contact Chris Acy, the AIS Coordinator for the Winnebago Waterways Program covering Fond du Lac, Calumet, and Winnebago Counties at (920) 460-3674 or chris@fwwa.org!

Winnebago Waterways is a Fox-Wolf Watershed Alliance program. The Fox-Wolf Watershed Alliance is an independent nonprofit organization that identifies and advocates effective policies and actions that protect, restore, and sustain water resources in the Fox-Wolf River Basin.

Photo Credit: Paul Skawinski, T. Lawrence, NOAA